How many U of T professors do you know who have been arrested and interrogated by the KGB? Now you know one.

Baņuta Rubess is an assistant professor, teaching stream, with the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Centre for Drama, Theatre & Performance Studies.

Her life story, as well as her father’s, could easily be the subject of a hit Broadway show, or a blockbuster movie.

She’s an accomplished playwright and director with several successful productions in North America and Europe, as well as a published author. So how did a theatre artist wind up being questioned by the KGB?

That’s the subject of a book she is currently writing called Tell No One, which explores the personal cost of being under surveillance.

In the 1970s you couldn’t enter the Soviet Union except on a short tourist visa, and all of your movements were very restricted.

The daughter of Latvian refugees after World War Two, she first visited Latvia in the 1970s when the country was still part of the Soviet Union.

“In the 1970s you couldn’t enter the Soviet Union except on a short tourist visa, and all of your movements were very restricted,” says Rubess, who was born in Toronto, grew up in Germany and later returned to Toronto as a teenager.

“I was brought up by people who said, ‘You're living in exile. You're not really Canadian, you're Latvian, but you can't go there, it’s not safe. But you must stay Latvian because there are less than two million of us.’ We were always conscious of the possibility of extinction.”

By the late 1970s, Russia was slightly more accessible to foreign travelers and scholars. “But at the same time the KGB had an active interest in sowing discord among ethnic communities,” she says.

I was identified as a persona non grata — a threat to the Soviet Union. And I was for sure. I will accept that. I totally opposed it. But sitting across from an KGB interrogator, you don't think that's going to happen to you when you're a kid from North Toronto Collegiate.

In 1978, while studying at Queen’s University, Rubess was named a Rhodes Scholar in just the second year that women were eligible to apply. She set her sights on studying in the Soviet Union, but before that took place she had returned to Latvia where she was arrested, interrogated and harassed by the KGB as a 23-year-old graduate student.

“It was very scary, she says. “It was a small room with one table and two chairs.” To her shock, an agent opened a notebook and described her movements back in Canada as well as her travels abroad.

“People were informing on me when I lived in the West,” she says. “They had been watching me since I was 18. The world changed for me at that moment.

“I was identified as a persona non grata — a threat to the Soviet Union. And I was for sure. I will accept that. I totally opposed it. But sitting across from an KGB interrogator, you don't think that's going to happen to you when you're a kid from North Toronto Collegiate.”

In addition to her own story, Tell No One also examines the impacts of being under surveillance today.

“Being surveyed is so much more prevalent in terms of social media and data on your phone,” says Rubess. “Many of our international students that I encounter at U of T have legitimate concerns if they're from a country that practices intensive surveillance of its citizens.”

My father was sent off at the end of the war with thousands of other young Latvian men to join the German army. Soon after he arrived, his company surrendered to the allies and he ended up in different POW camps from age 17 to 19. The thing that he says saved his life was yoga.

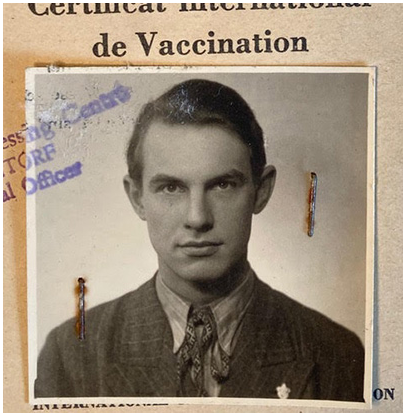

If Rubess’ story sounds harrowing, her father’s story of survival is nothing short of remarkable.

Her earlier book, Bruno Slept Here is part memoir, part novel about her father’s involvement with a secret yoga club in Nazi-occupied Riga, Latvia’s capital, in 1942 when he was just 17. The book was released in Latvia in December, and Rubess is currently looking for a North American publisher for an English version.

“My father was sent off at the end of the war with thousands of other young Latvian men to join the German army,” she says. “Soon after he arrived, his company surrendered to the allies and he ended up in different POW camps from age 17 to 19. The thing that he says saved his life was yoga.

“This was a secret club because both the Nazis and the Soviets were against anything that smacked of spiritualism, so they suppressed all yoga practitioners.”

To research the book, Rubess returned to Europe to map her father’s escapes and imprisonments from Poland to Belgium, exploring themes of trauma and resilience. “The book is really about how to not collapse in a collapsing world,” she says.

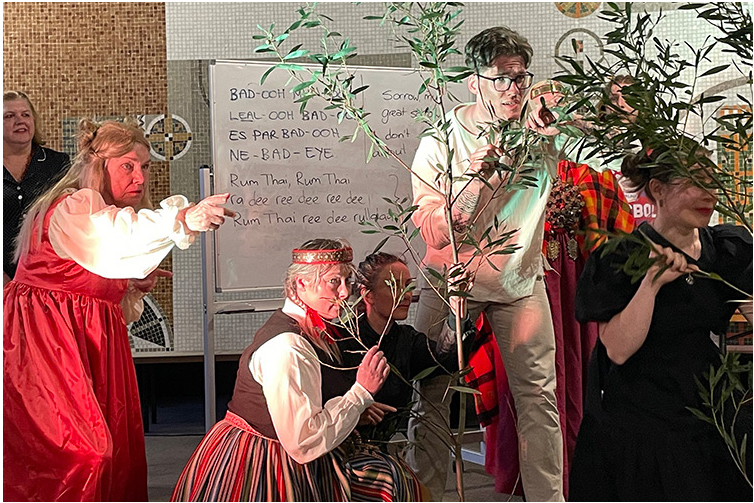

In addition to these two books, Rubess continues to be active in theatre productions — her most recent being Dickens Street: The Other, a play she was invited to create by a Latvian theatre company in Australia.

“There's an amazing Latvian cultural community building in Melbourne and they wanted to celebrate its history,” she says, noting the Melbourne Latvian House has housed a vibrant community theatre scene ever since the first Latvian refugees arrived 70 years ago.

Running in early 2024, audiences followed one of three characters around the building. Each one celebrated the efforts of the Latvian diaspora to resist assimilation and overcome the PTSD of the older generation.

Theatre is always community focused, because no one can do it alone and no one can make theatre without an audience.

“What I loved about the show was the impact it generated, reviving the local community, and raising awareness among their fellow Australians,” says Rubess. “That led to new creative projects by the people involved in the show.”

Moving from the stage to the classroom, Rubess tries to pass on her lived experiences and her approach to theatre’s powerful influence to her students.

“From my very early attraction to theatre, I have always been asking, ‘What can theatre do to change the world, to improve the world?’” she says.

The recent U.S. election and subsequent tensions have reminded Rubess of powerful lessons that theatre teaches us, especially in times of crisis.

“What you're really trained to emblazon on your heart is that the show must go on no matter what awful things are happening,” she says. “You have to know how to compose yourself, how to control yourself physically, how to breathe. That will help you in in any kind of traumatic situation.”

Another important lesson — theatre is community, a place of tremendous connection and encouragement.

“Theatre is always community focused, because no one can do it alone and no one can make theatre without an audience.”